Reclaiming Our Roots: America’s Native Food Trail in VirginiaAmplifying Indigenous Womens’ Voices3/10/2025

Roanoke Foodshed Network and Partners present:

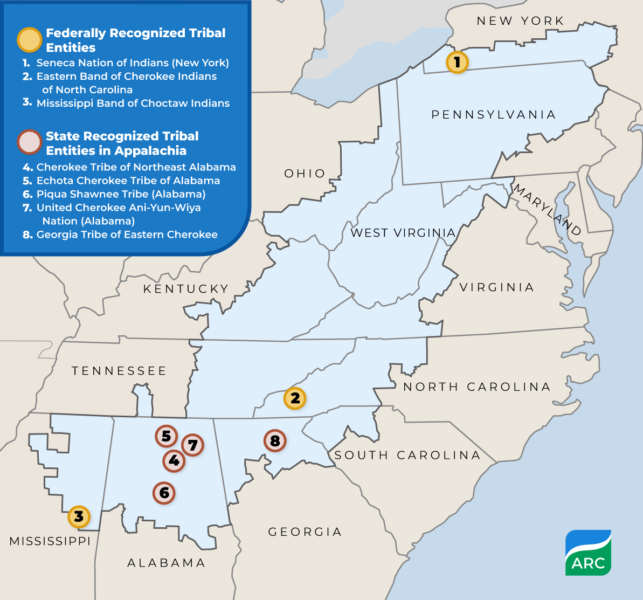

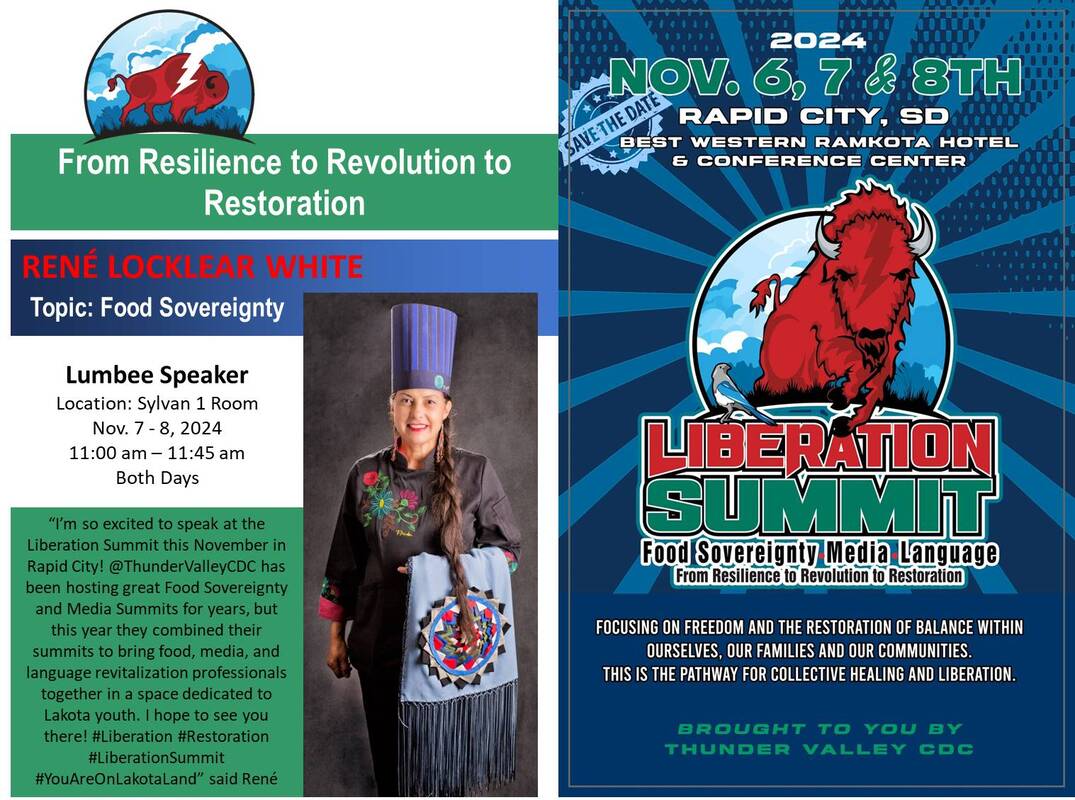

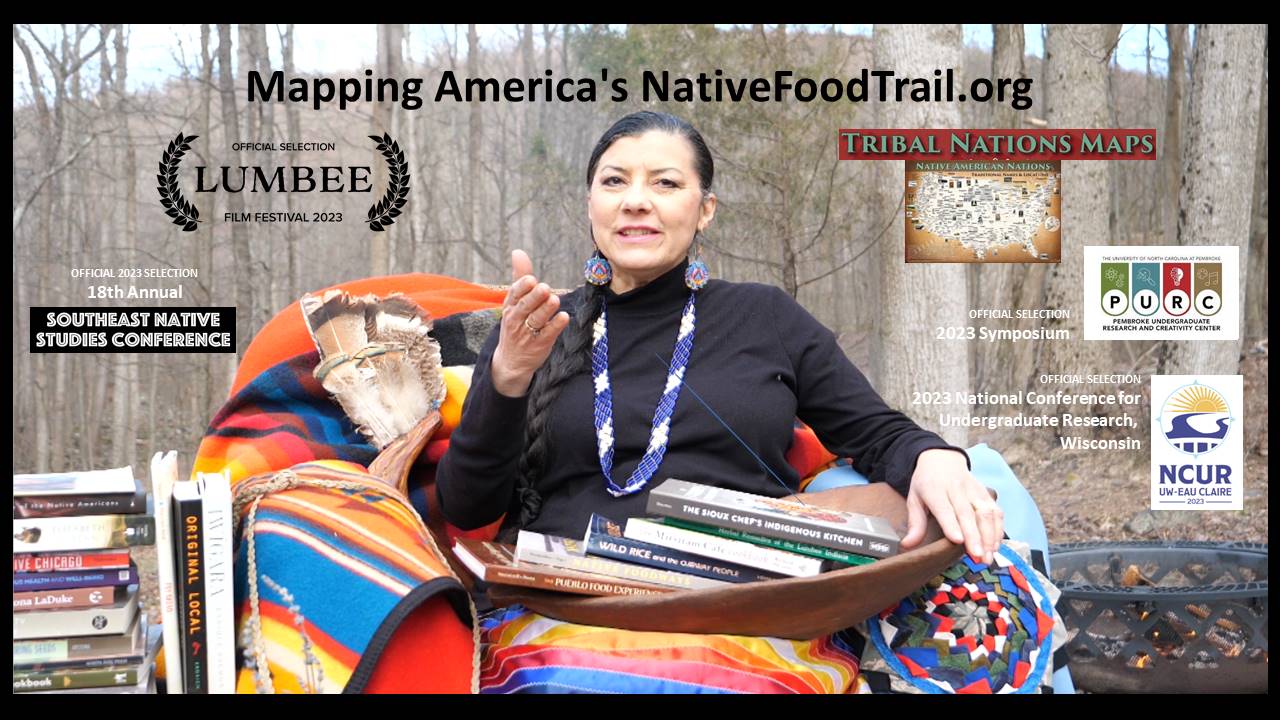

Join us for this Native foodways event where two Indigenous women leaders share their knowledge and experiences related to food sovereignty and traditional dietary practices. This unique event brings the Indigenous past to the plate, fostering a deeper understanding of the rich culinary traditions that have sustained communities for generations. Sample Virginia’s culturally significant dishes, bring and share seeds, and participate in fun food activities from preparation and connection to exploring the sacredness of food as a source of healing and heritage. Victoria Persinger Ferguson is an enrolled citizen of the Monacan Indian Nation of Virginia and is a graduate of Marshall University. Victoria has a background in researching science methodologies to support historical information. She has spent 30 years seeking first-person documentation and archaeological information to help explain and support theories on the daily living habits of the Eastern Siouan populations up through the early European colonization period. She has written and presented work at Virginia Tech, Washington and Lee, Sweet Briar College, James Madison University, Mary Baldwin, and various archaeological conferences. She currently serves as the Program Director for Historic Solitude/Fraction on the campus of Virginia Tech. René Locklear White, as an active member of her Lumbee Tribe, retired Air Force Lt. Col., and Virginia resident, she has dedicated her life to promoting Indigenous culture and wellness. René earned a Masters in Diplomacy and three Bachelors in Mathematics, Fine Art, and American Indian Studies from her tribal University of N.C. at Pembroke. She is co-founder of the Native American non-profit Sanctuary on the Trail. Through this 501(c)3, she and her husband Chris help leaders first, bring recognition to the contributions of Indigenous Peoples to reduce suffering in the world. She has written and presented food sovereignty work in Virginia, D.C., North Carolina, West Virginia, Minnesota, and South Dakota. As an Indigenous chef, she produced a short film, “Mapping America’s Native Food Trail” and NativeFoodTrail.org. These remarkable women will highlight the cultural significance of Native foods, illustrating how these practices connect us to our heritage and promote sustainable ways of nourishment that are vital not only for individual healing but also for the collective well-being of our communities. What Native Food(ways) in Appalachia could revitalize America's diets to address contemporary health challenges? Let's visit Appalachia's eight (state and federally) recognized tribes: 1. NY - Seneca Nation of Indians 2. NC – Eastern Band of Cherokee 3. MI – Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians 4. AL – Cherokee Tribe of Northeast Alabama 5. AL – Echota Cherokee Tribe of Alabama 6. AL – Piqua Shawnee Tribe 7. AL – United Cherokee Ani-Yun-Wiya Nation 8. GA – Georgia Tribe of Eastern Cherokee How does the varied topography of the Appalachian region and each individual Tribe’s culture determine which kinds of foods can help us heal?

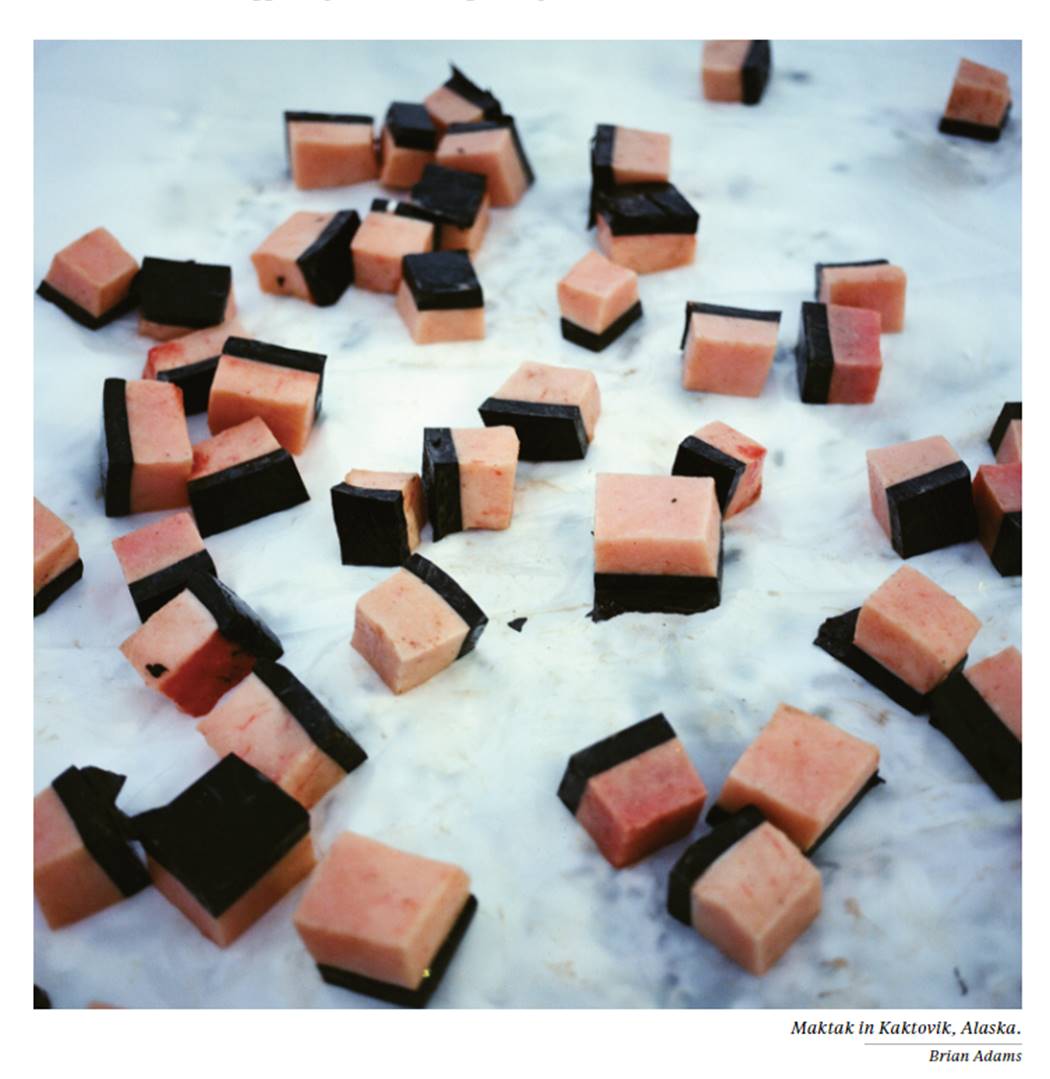

Do the Tribes living in Appalachia mountains have pawpaw fruits, mushrooms, wild onions, berries, and black walnuts? Do the Tribes living in the Appalachia deep valleys enjoy ramps, sunchokes, plums, fiddleheads, cherries, and purple dead-nettle? Do the Tribes near Appalachia river systems still depend on the local fish and wildlife as food sources? Do they also depend on elderberry, dandelions, goldenseal, chickweed, and chicory? What Native Appalachia foods are good for nutrition and wellness to include: wild game, root crops, acorns, persimmon, hickory nuts, chestnuts, blueberries, baby pinecones, sunflowers, violets, sumac, garlic mustard, grain-bearing grasses, and coveted wild ginseng? We will keep you posted on what we discover. About the Summit.This summit marks a shift from Resilience to Revolution to Restoration. We often celebrate the truly incredible resilience of our Lakota Oyate and of Indigenous peoples of all nations, but we are not stuck in resilience. We are moving towards something more forward-thinking. Revolution is part of our identity. We come from a long line of warriors, healers and leaders who lived and died to ensure that we would still be here all these generations later, singing our songs and speaking our language. This summit is part of us: it is an expression of our responsibility to fight for freedom and find our Liberation. Native Food Trail Co-Founder.#Liberation #Restoration #LiberationSummit #YouAreOnLakotaLand An Inupiaq writer describes the fellowship and delight of a Native supper.Laureli Ivanoff Any time I ask Timm, my husband, if he wants nikipiaq for supper, he says yes. On a recent Sunday, the northeast wind blew cold Arctic air against our home, the woodstove crackled steady all day, and I wanted Native food. The entire spread, shared with my Dad and my brother’s family, is a meal made up of fare gathered, plucked or hunted throughout the year, and harvested for nights like this. Timm was at the kitchen island, cutting clean the surface of a block of beluga maktak the size of his hand. We saw the motion-sensing light turn on outside. It was Dad showing up for supper, his footsteps crunching loud on the snow on the hollow deck. Our son, Henning, promptly squealed and ran to hide. The door opened. “Where’s my mon?” Dad said, using his nickname for Henning as he smiled and looked around for him. As fast as he had run to hide, Henning ran out again, laughing, to give his Papa a hug. My brother, Fred Jay, and his wife, Yanni, took off their boots and jackets, then walked into the kitchen carrying a plastic food storage container full of bowhead maktak and a gallon-sized Ziploc bag of dried pink salmon. In Unalakleet, we aren’t bowhead whale hunters, as the large whales do not migrate through the shallow ocean waters of the Norton Sound. But my brother is adept at trading with acquaintances on St. Lawrence Island, where they have long traditions of hunting the 60-foot whales, and he always seems to have the maktak in his freezer — maktak valued both because of our own inability to harvest the rich food and for its mild flavor. He trades dried pink salmon for the prize. “They’re not real big, but they’re good sized.”Our table was set with two ulus, several small bowls and saucers for seal oil, and five deconstructed cracker and cereal boxes, which would serve simultaneously as cutting boards and oil-soaking plates. Timm and Fred Jay picked up the ulus to cut the three Dollies from the porch into bite-sized pieces. We loaded our cardboard plates with dried fish, dried ugruk meat, bowhead maktak, carrots, boiled potatoes we’d harvested from our garden last fall, quaq, or frozen fish, and other picked-from-the-land-and-water delights. “Ooh, popped eggs,” Fred Jay said when he noticed the large bowl full of butter-yellow steamed eggs we’d taken from herring bellies last spring. The herring had arrived back in May, after the ice was gone. Just like every spring, we’d boated 18 miles down the coast, to the black, volcanic-rock shores of Shorty Cove, to harvest the eggs they’d laid on kelp. But the herring hadn’t yet spawned. The silvery fish were stacked on top of one another, three feet out from the edge of the beach, the females eager to release their eggs and the males their milt. So we picnicked in the warm sunshine, then collected their eggs a different way. My cousin Allen scooped his dip net, usually used for silver salmon fishing, into the cold ocean water and piled herring into a small, gray fishing tub. Timm and I sorted the still-wriggling fish. We threw the live males back into the ocean. The females with full bellies we grabbed with both hands and literally popped open their swollen bodies to harvest the rich, sticky eggs inside — a carnival-like chore that leaves your face tacky with sea water and your hands covered in a layer of gummy eggs that even soap can’t remove. We gathered the eggs in a clean, white one-gallon bucket and placed the spent bodies back in the water to nourish the ocean. Once home, we vacuum sealed the eggs in quart-sized bags, the perfect amount for a meal. Two days later, our family boated back down to Shorty Cove to harvest black trash bags full of eggs the herring had spawned since the last time we were there, translucent dots thickly coating the green fingers of seaweed that clung to the rock shore. The eggs pop between your teeth like Pop Rocks candy, and the seaweed embedded inside the thick layers of eggs adds flavor and rich nutrients. The night we had my family over for dinner, offering both spawned-on-seaweed and popped herring eggs felt like indulgent dining, like ordering both French fries and onion rings with a burger. Closing my eyes, I enjoyed the combination of salt, spice and fat, and went back for more.“There’s tukaiyuks, too,” I said, making sure everyone got some greens to go with their protein and starch. Placing tukaiyuks on my plate, I sprinkled a bit of salt on the oily, still fresh-looking leaves. My plate full, I used my thumb and forefinger to squeeze a few leaves of the parsley-flavored tukaiyuk into a cold piece of quaq, the tips of my fingers covered in seal oil — my favorite combination. The meat wasn’t frozen solid, making it smooth and easy to chew. The salt on the greens rounded out the flavors of herbed fish and soul-calming oil. On my cardboard plate was a small pile of thinly sliced, half-inch pieces of bowhead whale maktak. I dribbled a small amount of soy sauce and a smaller amount of chili garlic sauce onto the pale pink fat and black skin and savored my first bite. The fat was tender and buttery, the skin chewy and firm. Closing my eyes, I enjoyed the combination of salt, spice and fat, and went back for more. After crunching on herring eggs and carrots and filling up with dried ugruk meat, I noticed that everyone was slowing down, so I got up to start the kettle and pull out the tea. A quart-sized Ziploc bag of frozen salmonberries thawed on the counter. We had picked them in July, after driving our four-wheeler to tundra just above the tidal flats that lie down the hill from our home. I dumped the orange, tangy, not-quite-thawed berries into a bowl, and, as I chopped and separated them with a fork, I smiled. All throughout my childhood, I heard my mom or my grandma chop frozen berries after a nourishing meal of nikipiaq. It felt good to do this simple, loving act, just like them. Laureli Ivanoff is an Inupiaq writer and journalist based in Uŋalaqłiq (Unalakleet), on the west coast of what’s now called Alaska. Her column “The Seasons of Uŋalaqłiq” explores the seasonality of living in direct relationship with the land, water, plants and animals in and around Uŋalaqłiq. Join us for the 5th annual Lumbee Film Festival will take place July 6 to July 8, 2023 in Pembroke, NC during Lumbee Homecoming. "The Lumbee Film Festival showcases bold, original new films made by Native Americans, Indigenous Filmmakers, and American Indians, especially members of the Lumbee Tribe living in North Carolina and across the United States," according to Cacalorus.org More about my short film selected for the Lumbee Film Festival please see details at https://www.cucalorus.org/lumbee-film-festival/ Location: James A. Thomas Hall University of N.C. at Pembroke 333 Braves Drive Pembroke, NC 28372 “Each year the Lumbee Film Festival gets better and better. I am so excited about this year’s lineup of short and feature films. Some are traditional and some have us thinking out of the box. Some are local and some are far away. Just like in real life. Something for everyone. Come join us. You will be glad you did,” – Kim Pevia, Festival Director The Lumbee Film Festival is a partnership between the Lumbee Tribe of NC and the Cucalorus Film Foundation. For questions about the Lumbee Film Festival, email [email protected] or [email protected]. Other Film Screenings & Festivals for "Mapping America's Native Food Trail"5th Annual Lumbee Film Festival

Pembroke, N.C. July 6-8, 2023 National Conference for Undergraduate Research (NCUR) University of Wisconsin-EAU Claire, WI April 13-15, 2023 2023 UNCP Pembroke Undergraduate Research and Creativity Center (PURC) Symposium Pembroke, N.C. April 12, 2023 18th Annual Southeastern Native Studies Conference Pembroke, N.C. March 30-31, 2023 Audio interview with Lumbee Indian H. Dobbs Oxendine. Jr. and the Old Foundry Restaurant in Lumberton N.C. Home of the Lumbee Indians of North Carolina.

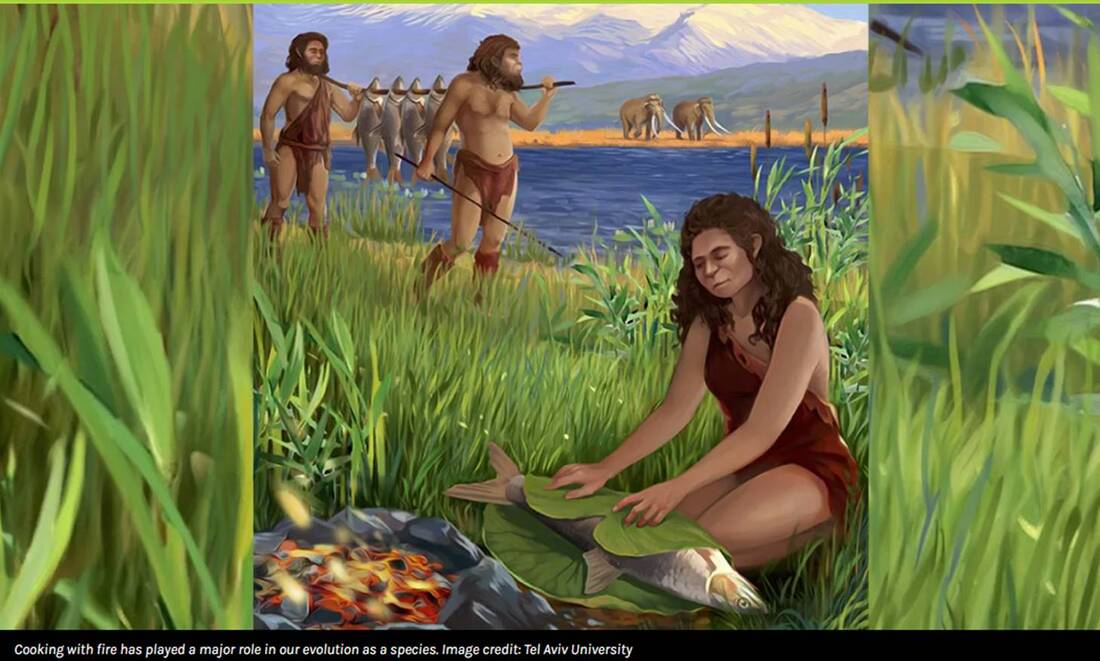

Ben Taub IFL Science The gigantic carp wasn't cooked over an open flame, and may have been carefully baked in an earthen oven.Archaeologists in Israel have discovered evidence of what may be the first-ever baked fish supper. After analyzing the remains of an enormous extinct carp, the study authors concluded that the animal was carefully cooked at a low-to-moderate heat 780,000 years ago, pushing back the earliest use of fire to prepare food by over 600,000 years. Mastery of fire is seen as a major milestone in human evolution as it allowed our ancient ancestors to cook and digest food more easily, leaving more energy available for cognitive development. According to the study authors, cooked fish in particular may have facilitated brain growth and sharper intellect in extinct hominid species, laying the groundwork for our present acumen and culinary skills. “Although fish can be eaten raw, cooked fish are more nutritious, safer to eat, easier to digest and, when cooked by steaming or baking (but not grilling), they retain their [docosahexaenoic acid] and eicosapentaenoic acid contents,” they write. “When fish cooking first began, however, is still unknown and there is no consensus as to when hominins first developed the ability to control fire and cook.” While some evidence exists to suggest that Homo erectus may have figured out how to use fire by 1.7 million years ago, it’s unclear if they utilized it for food preparation. Until now, the earliest direct evidence for cooking fires had been attributed to ancient communities of Neanderthals and modern humans some 170,000 years ago. However, carp teeth discovered in a layer of sediment dated to 780,000 years ago at the Gesher Benot Ya'aqov (GBY) archaeological site suggest that earlier hominid species were already baking their fish in the more distant past. Using X-ray powder diffraction to analyze the size and structure of enamel crystals within these teeth, the researchers determined that they had been cooked at a controlled temperature of less than 500°C (932°F). “Identification of the cooking method practiced by the GBY inhabitants is indeed a challenge, especially since no traces of cooking apparatus have been preserved at the site,” write the study authors. “Nonetheless, ethnographic and experimental studies indicate that fish cooking requires production of low–moderate heat (300–500°C [572–932°F]), while preventing fast cooling or direct burning. One possibility, therefore, is that the GBY inhabitants used some kind of earth oven that maintained a temperature below 500°C to cook their fish.” Commenting on these findings in a statement, study authors Dr Irit Zohar and Dr Marion Prevost explained that “the large quantity of fish remains found at the site proves their frequent consumption by early humans, who developed special cooking techniques.” “These new findings demonstrate not only the importance of freshwater habitats and the fish they contained for the sustenance of prehistoric man, but also illustrate prehistoric humans' ability to control fire in order to cook food, and their understanding the benefits of cooking fish before eating it." The study is published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution. By Amanda Fiegl, Smithsonian Magazine

Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian Mitsitam Native Foods Café 4th St. & Independence Ave. SW Washington, D.C. http://www.mitsitamcafe.com/ “Mitsitam” means “Let’s eat!” in the Native language of the Delaware and Piscataway peoples. The museum’s Mitsitam Native Foods Cafe enhances the museum experience by providing visitors the opportunity to enjoy the indigenous cuisines of the Americas and to explore the history of Native foods. The Cafe features Native foods found throughout the Western Hemisphere. Each of the five food stations—Contemporary Native; Mountains and Plains; Native Comfort; Oceans, Sea and Streams; and The Three Sisters—depict regional lifeways related to cooking techniques, ingredients, and flavors found in both traditional and contemporary dishes. Selections include authentic Native foods, such as traditional fry bread, as well as contemporary items with a Native American twist.

|

Mapping America's Native Food Trailto reduce suffering Categories

All

|

Special Recognition to our friend Dr. Rudy Coronado Jr. for his relentless friendship and advice

Map Partner: Aaron Carapella - Tribal Nations Maps (949) 415-4981 [email protected]

This project is a result of a PURC Fellowship from the University of N.C. at Pembroke and

Endorsed by the Native American non-profit Sanctuary on the Trail 501(c)3

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by iPage

Map Partner: Aaron Carapella - Tribal Nations Maps (949) 415-4981 [email protected]

This project is a result of a PURC Fellowship from the University of N.C. at Pembroke and

Endorsed by the Native American non-profit Sanctuary on the Trail 501(c)3

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by iPage

Fair Use Notice

This website may contain copyright material, the use of which has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. If we make such material available, it is in an effort to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economics, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a “fair use” of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposed. Our non-profit’s transformative mission is to provide new decolonized content to help educate the general public and help reduce suffering. Our information can be awareness provoking using factual content.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed